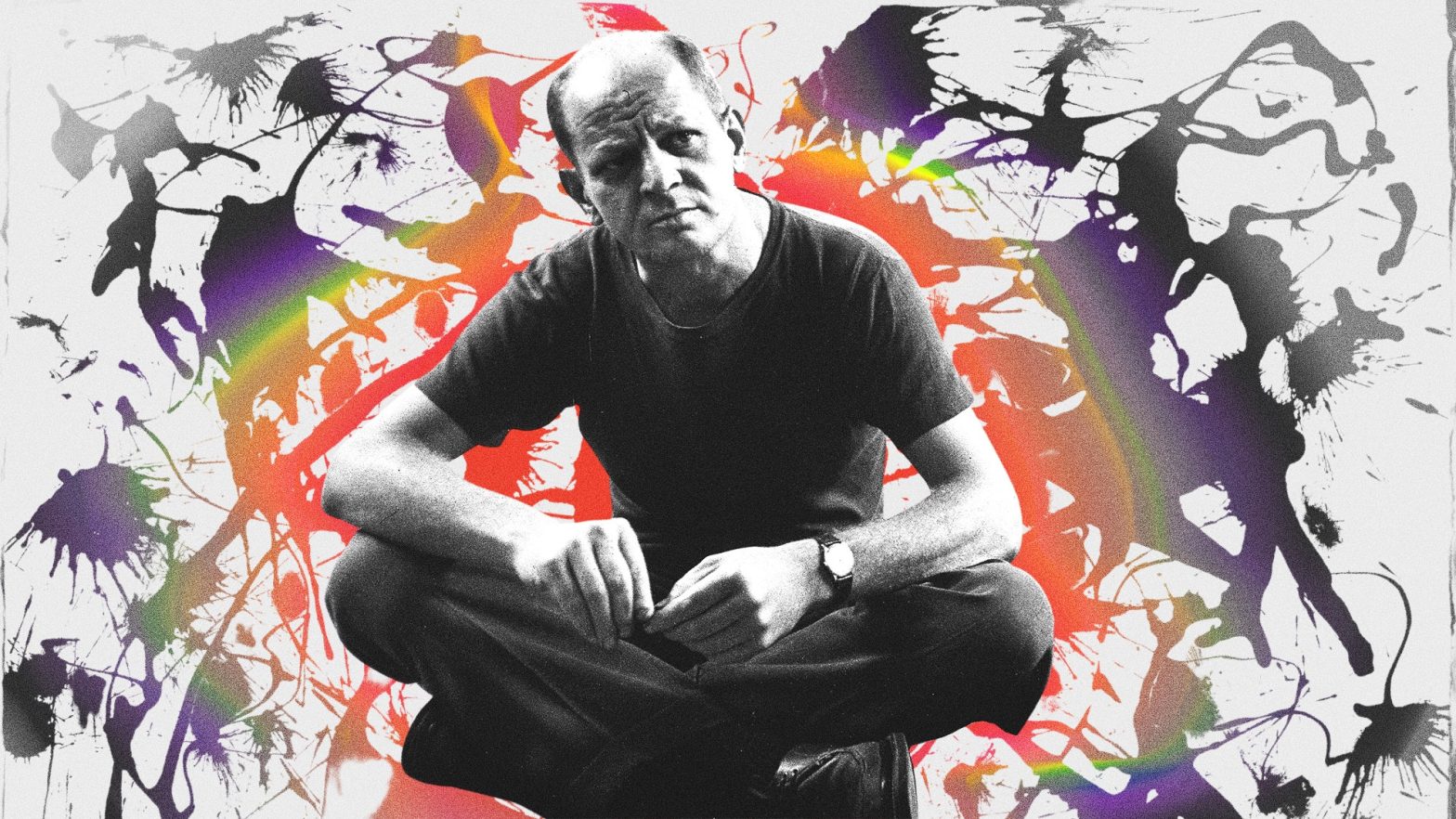

Did a Secret Manhattan Cult Drive Jackson Pollock to His Death?

Published By admin

I had been living on the Upper West Side for decades when, in the 2010s, I realized I had been entirely unaware of what was, in effect, an alternate society in our midst, hidden in plain sight. Founded in 1957, the Sullivan Institute for Research in Psychoanalysis was a utopian community of a few hundred people in which therapists and their patients lived alongside each other in large group apartments. Its creators, the married psychotherapists Saul Newton and Jane Pearce, were influenced by the neo-Freudian psychiatrist Harry Stack Sullivan, who believed that psychological problems were inherently about interpersonal relationships.

They created a parallel world, living by precise rules and precepts almost entirely at odds with those of mainstream society. Under the direction of their therapists, the Sullivanians were trying to create a utopian world based on the principles of free love, collective living, self-actualization, and a commitment to socialism. In one sense, the group partook of the counterculture of the 1960s, the decade of sexual liberation and communal living. Yet most of the era’s communes—an estimated three thousand in the 1960s and ’70s—lived in isolation in such places as rural Oregon and Vermont. This group was composed almost entirely of high-performing urban professionals—doctors, lawyers, computer programmers, successful artists and writers, professors—who went to normal jobs by day but returned in the evening to a very different and highly secretive world built around fellowship, polygamous sex, radical politics, and political theater.

During its different phases the Sullivan Institute encapsulated many of the major themes—and pitfalls—of twentieth-century counterculture.

In its first ten or fifteen years, this novel form of treatment, which encouraged patients to experiment sexually, trust their impulses, and break free of family dependency relationships, appealed to many artists and creative individuals. There were lots of patients who were not famous artists: men trapped in dull jobs or suffering from loneliness; frustrated wives, whose therapists encouraged them to leave their husbands, have affairs, and hand over the care of their children to others so that they could explore their own creative potential.

Psychotherapy and art in the 1950s were a good fit. It was natural for artists to turn to therapy as part of a process of contending with—or throwing off—their past and remaking themselves into the people they wanted to become. These were people who, after all, were questioning virtually every assumption in art: Does art have to represent something? Do I need to paint on an easel? Do I need to paint with a brush? Do I need paint at all? And so it seemed quite natural for them to question the traditional assumptions of mainstream American life: What is marriage? What is family? Is sexual fidelity necessary? Psychotherapy appeared to offer the prospect of tapping into the world of the unconscious and freeing the repressed forces and desires that lay buried there. Isn’t that what artists needed to do in order to unlock the full extent of their talent? It was easy to believe that a man (in those days, artists were usually men) who timidly obeyed middle-class convention in his personal life might also limit himself and fail to realize his potential in his artistic life.

The art world was fertile ground for a therapy that was rebellious and anti-conformist. “There are no rules,” as Helen Frankenthaler (not herself a Sullivanian patient) put it. “That is how art is born, how breakthroughs happen. Go against the rules or ignore the rules. That is what invention is about.” Sullivanian therapy, in particular, which urged its patients to follow their creative desires and throw off the weighty obligations and expectations of society, marriage, and family, was particularly appealing to people in this milieu. “[Before that] I could never take my feelings seriously; my impulses,” the famed art critic Clement Greenberg said. “I was always looking to the world to get my bearings.”

During Greenberg’s first months of therapy, in the summer of 1955, his therapist, Ralph Klein, moved out to stay with Jane Pearce and Saul Newton at their summer home at Barnes Landing in Amagansett. Greenberg, unable to accept a lengthy separation from the therapist he had begun to see every day, began inviting himself to stay with friends on Long Island, in particular the artist Jackson Pollock and his wife, the painter Lee Krasner, who lived in Springs, only a few miles from Klein, Newton, and Pearce.

Pollock was in a period of deep crisis, one that Greenberg himself had helped create. A lifelong alcoholic, Pollock, with Krasner’s help, had managed to remain sober between 1947 and 1951, one of his periods of greatest productivity. But in 1954 he decided to take his art in a new direction, moving away from the drip paintings that made him famous.

Greenberg was unimpressed, describing Pollock’s 1954 show at the Janis Gallery as “forced, pumped, dressed up.” His review seemed to imply that Pollock had lost his way: Pollock “found himself straddled between the easel picture and something else hard to define, and in the last two or three years he has pulled back.” In the same essay, Greenberg seemed to place the crown of America’s preeminent painter on the head of Clyfford Still, calling him “one of the most important and original painters of our time.”

Content retrieved from: https://www.gq.com/story/jackson-pollock-sullivan-institute.